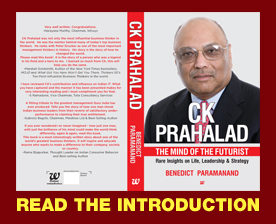

Select excerpts from a recent interview with Mr. Ratan Tata, former Chairman of the Tata Group, by Benedict Paramanand, Editor of ManagementNext magazine, for the forthcoming book ‘CK Prahalad’s Impact and Influence on Indian Business Leaders’ to be published by Westland this year.

Select excerpts from a recent interview with Mr. Ratan Tata, former Chairman of the Tata Group, by Benedict Paramanand, Editor of ManagementNext magazine, for the forthcoming book ‘CK Prahalad’s Impact and Influence on Indian Business Leaders’ to be published by Westland this year.

What has been your experience with the Bottom-of-the Pyramid market?

Unlike the Bombay Club members who were demanding level playing field, I always felt that there was a big market that we had to address. Prahalad also enunciated that in a very much more defined way and described the market and opened everybody’s eyes to the potential in an unqualified sort of view. If you applied Prahalad’s hypothesis, the size of India’s market is 600 million people which is phenomenally large and a significant market, much bigger even than China’s. But you had to address that market with products and mindset that was serving that market which many manufacturers, including the Tata’s, were not looking at before. So Prahalad’s hypothesis is exceedingly important both to these markets and also to Western markets which are looking for newer markets than they had. His hypothesis was exceedingly a significant contribution to business thinking.

My own experience with that segment of the market has been somewhat disappointing because what has also been evident, which I don’t think Prahalad addressed, is a sense of pride of not being seen to be at the base of the pyramid. So, it amazes me at the number of high value items that are sold even at great distress, but they will not take the items that are designed for them because that would look as though they were buying something because they couldn’t afford to get a better one.

Nano suffered from that perception?

Nano suffered greatly from that perception mainly because Tata Motors chose, I think, the soft option of saying ‘It’s the cheapest car rather than it’s the best value car.’ I think we did that to ourselves but, yes, it became an issue. ‘I don’t want to be seen in the cheapest car, what will my neighbors say?’ It gives you everything that you need. And it should not be sold because of price.

What is your dream for India?

I have a couple of aspirations or passions. One is, I would dream of being a country of equal opportunity which it is not today. It is cut and quartered into rich, poor, religious communities, castes and so often it’s an issue of ‘whose son you are; whose name you use’ etc. I dream that a person who is poor, who has tremendous capability, or ability, can have the same chances as somebody who is rich.

The other dream I have is a country where all people are equal in the eye of the law and that it is not ‘don’t you know whose son I am?’ ‘You can’t touch me and the law for me is different from the law from you.’

Those two dreams unfortunately are going in the opposite way today. They are getting more pronounced in the opposite direction and so I have very serious frustration in terms of where we will be in another 10 years. My concern, I have said it publicly, I have been chastised for it, that we are becoming more and more like a banana republic; that we take revenge on somebody because he crossed my path.

Those would be the two dreams I would think of – a dream that everybody with merit would be viewed equally and that the law would apply to everybody in the same way. Nobody should feel that they are above the law.

What is your legacy to Indian business not just to the Tatas?

I don’t know that I have a legacy to leave behind to define what that legacy is. What I have tried to do is run an ethical organization and values and to hold on to those values throughout, even at the cost to us and to the best of my abilities to run the businesses in an ethical manner, to be fair to our customer and our stake holders.

But I think it’s for others to decide if there is a legacy or not. The environment is changing constantly and the only legacy I could say I left behind is an organization that has tried to practice what it has preached and not speak with two mouths. I hope that continues because that’s the legacy the founder left behind which I have tried to follow, it’s not my legacy. My legacy has just been to safeguard it, cherish it and pass it on to the next generation.

What is the biggest challenge for the next generation? It’s difficult to say, but in the country that we are in today, and the direction we are moving , there is a great deal of hypocrisy, great deal of more corruption than there was in my time and therefore much more difficult to do business now than in my time. To do business ethically now is exception rather than the rule.

The challenge is going to be for people to go to bed at night and say, ‘I didn’t succumb. Business challenges are going to be the same, the method of competition has changed, and it is now what is done in the dark corridors in Delhi in terms of forging policy that suits him, and not you, instead of fighting in the market place.

What has been your experience with the Bottom-of-the Pyramid market?

Unlike the Bombay Club members who were demanding level playing field, I always felt that there was a big market that we had to address. Prahalad also enunciated that in a very much more defined way and described the market and opened everybody’s eyes to the potential in an unqualified sort of view. If you applied Prahalad’s hypothesis, the size of India’s market is 600 million people which is phenomenally large and a significant market, much bigger even than China’s. But you had to address that market with products and mindset that was serving that market which many manufacturers, including the Tata’s, were not looking at before. So Prahalad’s hypothesis is exceedingly important both to these markets and also to Western markets which are looking for newer markets than they had. His hypothesis was exceedingly a significant contribution to business thinking.

My own experience with that segment of the market has been somewhat disappointing because what has also been evident, which I don’t think Prahalad addressed, is a sense of pride of not being seen to be at the base of the pyramid. So, it amazes me at the number of high value items that are sold even at great distress, but they will not take the items that are designed for them because that would look as though they were buying something because they couldn’t afford to get a better one.

Nano suffered from that perception?

Nano suffered greatly from that perception mainly because Tata Motors chose, I think, the soft option of saying ‘It’s the cheapest car rather than it’s the best value car.’ I think we did that to ourselves but, yes, it became an issue. ‘I don’t want to be seen in the cheapest car, what will my neighbors say?’ It gives you everything that you need. And it should not be sold because of price.

What is your dream for India?

I have a couple of aspirations or passions. One is, I would dream of being a country of equal opportunity which it is not today. It is cut and quartered into rich, poor, religious communities, castes and so often it’s an issue of ‘whose son you are; whose name you use’ etc. I dream that a person who is poor, who has tremendous capability, or ability, can have the same chances as somebody who is rich.

The other dream I have is a country where all people are equal in the eye of the law and that it is not ‘don’t you know whose son I am?’ ‘You can’t touch me and the law for me is different from the law from you.’

Those two dreams unfortunately are going in the opposite way today. They are getting more pronounced in the opposite direction and so I have very serious frustration in terms of where we will be in another 10 years. My concern, I have said it publicly, I have been chastised for it, that we are becoming more and more like a banana republic; that we take revenge on somebody because he crossed my path.

Those would be the two dreams I would think of – a dream that everybody with merit would be viewed equally and that the law would apply to everybody in the same way. Nobody should feel that they are above the law.

What is your legacy to Indian business not just to the Tatas?

I don’t know that I have a legacy to leave behind to define what that legacy is. What I have tried to do is run an ethical organization and values and to hold on to those values throughout, even at the cost to us and to the best of my abilities to run the businesses in an ethical manner, to be fair to our customer and our stake holders.

But I think it’s for others to decide if there is a legacy or not. The environment is changing constantly and the only legacy I could say I left behind is an organization that has tried to practice what it has preached and not speak with two mouths. I hope that continues because that’s the legacy the founder left behind which I have tried to follow, it’s not my legacy. My legacy has just been to safeguard it, cherish it and pass it on to the next generation.

What is the biggest challenge for the next generation? It’s difficult to say, but in the country that we are in today, and the direction we are moving , there is a great deal of hypocrisy, great deal of more corruption than there was in my time and therefore much more difficult to do business now than in my time. To do business ethically now is exception rather than the rule.

The challenge is going to be for people to go to bed at night and say, ‘I didn’t succumb. Business challenges are going to be the same, the method of competition has changed, and it is now what is done in the dark corridors in Delhi in terms of forging policy that suits him, and not you, instead of fighting in the market place.

Recent Comments